First things first:

- Text formatting can be categorized as bold or subtle, depending on the desired effect.

- Mixing fonts can enhance readability.

- Less is more: Text formatting should highlight information and be used sparingly.

In Word, you can adjust font style and size or apply formatting such as bold, italic, underline, strikethrough, subscript, superscript, indents, colors, or even set text to all uppercase. This article shows you how to apply these formats and when it’s best to avoid them.

All tips provided here apply to the latest versions of Microsoft Word included in Office 365 and Office 2019.

Bold Text: An Attention Grabber

In typography, font weight refers to the “stroke width” of printed or virtual letters and characters. Many font families offer variations that incorporate different weights (regular or bold), widths (narrow or wide spacing between letters), or styles (regular or italic), such as Arial, Arial Narrow, and Arial Black.

The weight you choose impacts the text’s readability. The closer the letters are together, the darker the typeface becomes. Conversely, thinner fonts or excessive letter spacing create a lighter look, which can be harder to read.

Avoid formatting entire paragraphs in bold. Instead, use it for individual words or short phrases.

Italic Text: Slowing Down the Reader

Font posture refers to the straight or slanted orientation of a font, measured by the vertical stroke of the letters. Slanted fonts are referred to as italic.

Italicized text is generally harder and slower to read than regular text. To maintain readability, avoid using italics for long passages.

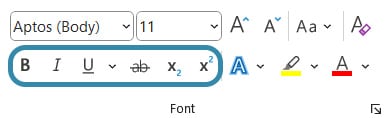

How to Format Text in Word

Everything you need to visually emphasize sections of your text can be found in Microsoft Word’s “Home” tab under “Font” on the left. Highlight the words or sections you want to format and click the corresponding icon.

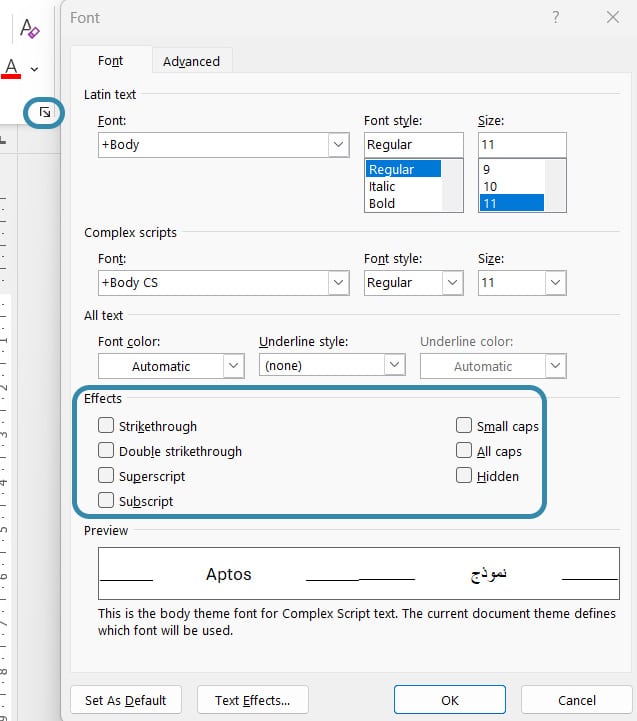

Additional text effects can be accessed by clicking the small arrow in the lower-right corner of the font menu.

Here, you can also specify whether the highlighted text should appear in small caps or ALL CAPS. For the latter, Windows users can use a handy shortcut: press Shift and F3 simultaneously to quickly toggle uppercase formatting on or off.

You might also be interested in these articles:

Bold vs. Subtle Formatting: The Effect Matters!

Bold, underlined, or colored words stand out from a passage of text before the eye has even reached the line in question. These are called “bold formatting” styles. In contrast, readers don’t notice the “subtle formatting” until the eye is in the line in question. Subtle formatting blends harmoniously into the text and can be achieved by italicizing or using small caps.

Since these styles produce distinct effects, avoid mixing bold and subtle formatting, as this creates typographical redundancy.

Mixing Fonts: Does It Make Sense?

Writing a lengthy text involves significant effort, whether it’s a research paper or a crime novel. However, engaging readers requires more than just good content—the text should also be well-structured and visually appealing.

One way to add structure is by mixing fonts. For instance, you could use a different font for headings than for body text. Quotes, captions, or footnotes can also stand out with distinct fonts. Studies show that mixed fonts facilitate skimming by helping the eye grasp text structure more effectively.

How to Mix Fonts

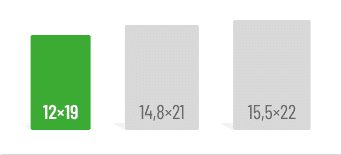

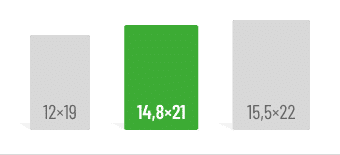

A basic rule, especially for academic texts, is to never mix more than two or three fonts. Using too many fonts can make your text look chaotic and disrupt the reading flow.

Microsoft Word offers a broad selection of pre-installed fonts. To achieve a cohesive look, stick to fonts from the same family. For example, the “Lucida” family includes serif and sans-serif options.

If you prefer to combine fonts from different families, ensure they contrast significantly. Serif fonts like Times New Roman and Garamond are too similar to create the desired effect. In academic contexts, prioritize professionalism; playful script fonts might work for a novel’s headings but are inappropriate for academic papers.

Did you know?

- Italic fonts without serifs are harder to read than italic fonts with serifs.

- Fonts deviate from optimal readability the further their weight differs from the standard (regular) weight.

- Font mixing dates back to ancient times; one of the most famous examples is the Rosetta Stone from 196 BCE.

Sources:

About the text markup:

- https://www.typolexikon.de/schriftauszeichnung/

- https://www.typolexikon.de/schriftstaerke/

- https://www.typolexikon.de/schriftlage/

To mix fonts:

Do you like our magazine? Then sign up for our GRIN newsletter now!